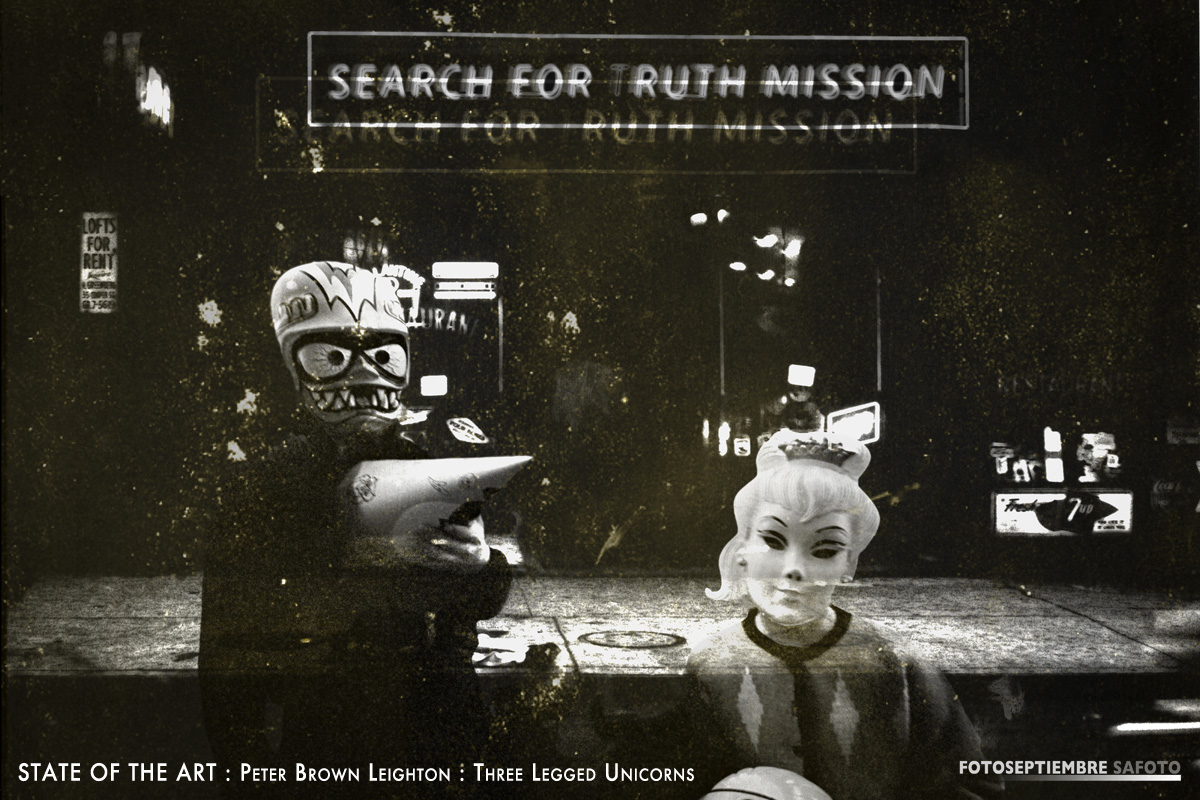

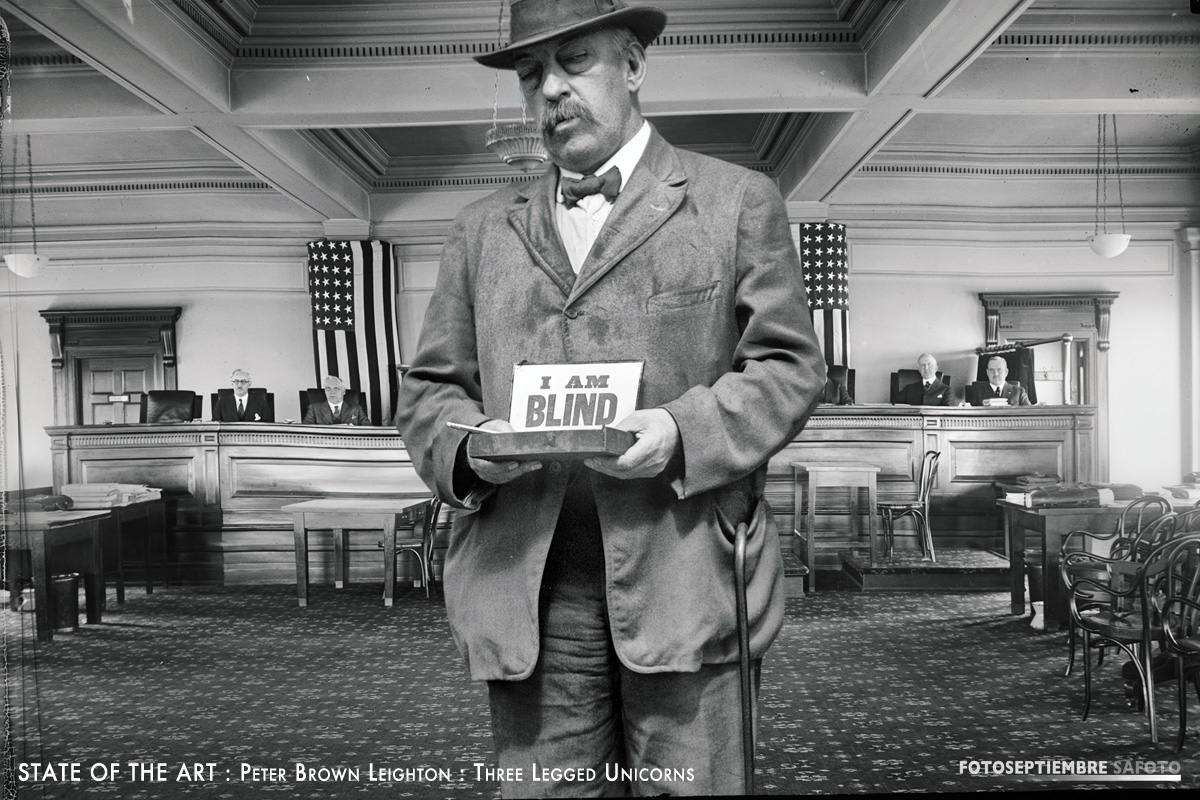

State Of The Art : Three Legged Unicorns : Peter Brown Leighton

#fotoseptiembre #safoto #stateoftheart #threeleggedunicorns #peterbrownleighton #larrylytle blackandwhitemagazine #photography #humanity #polity #sanantonio #lockhart #texashillcountry #texas

#fotoseptiembre #safoto #stateoftheart #threeleggedunicorns #peterbrownleighton #larrylytle blackandwhitemagazine #photography #humanity #polity #sanantonio #lockhart #texashillcountry #texas

State Of The Art

Three Legged Unicorns

Peter Brown Leighton

I’ve given a few interviews over the years. Below are a few excerpts from an interview conducted by Larry Lytle in preparation for a feature article in Black & White Magazine back in the mid twenty-teens.

L.L. You speak of your body of work as a bridge between the analog era and the newly developing digital path we are all treading. But you don’t really discuss the subject matter of the work. Obviously there are a lot possibilities to create a faux narrative that suits your “Mash-up” interests…It seems then that you see your work as serious social political commentary tinctured with a dram of ironic humor?

P.B.L. I’m a skeptical humanist, more interested in highlighting the absurdities of life than in speaking truth to power. I invite viewers to step inside an apocalyptic side show and leave it up to them to decide how seriously they want to take the performance.

I do agree that there are elements of social and political commentary woven into my work. There is no question that this project, starting as a personal examination of my life and times several years ago, has evolved into a kind of requiem for the American dream.

L.L. You mention the influence of the Auto-Destruction art movement on your mentor and on Pete Townsend. How did it affect you? Is there any part of the philosophy of Auto-Destruction in your body of work, besides the apparent desire by our culture to auto-destruct in number of ways today? I have to say that McGuire’s Eve of Destruction plays in my head as the background song for your series “Man Lives Through Plutonium Blast”.

P.B.L. Townsend and my mentor Tom excused their self-destructive tendencies by wrapping themselves in Gustav Metzger’s Auto-Destructive manifesto. I personally didn’t require, at least I thought so in my twenties, a high concept art movement to hide behind. In that regard, I was certainly more of a nihilist than they were. I truly didn’t believe that I would make it to thirty, when by that age Townsend and Tom were already cashing in on the bad boy personas they had crafted for themselves.

Today, of course, I’m in my seventies and have had a few more decades to think about things. I still am very careful about what I’m willing to believe in with absolute certainty, but I do fully embrace and am never less than captivated by the incredibly complex mystery that is humanity. I like to think my work reflects this perspective.

The last image in my series “Man Lives Through Plutonium Blast” is of an atom bomb detonating in Los Angeles. Its title “After Total War Can Come Total Living” was the tag line of a popular American advertising campaign that ran in magazines the mid-1940s as the tide of World War II began to turn. Ten years earlier, of course, this same statement could also have been printed on one of Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda posters. And these days, it wouldn’t be unusual to read that Steve Bannon had reportedly uttered the words at a Washington dinner party.

L.L. You stated that most of this work uses vernacular snapshots found at junk shops and so forth. I’d like to understand how this process works out. Are all the images altered, or do you find any that you can use off the shelf?

P.B.L. All of my images are composites, derived from found snapshots. My guiding principle has been to select images that aren’t visually compelling in and of themselves and combine them to give them a reason for being. The practical aspect of this approach has been that most of my source snapshots don’t cost much, because they aren’t considered all that collectible.

Therein, however, lies one degree of difficulty in doing this kind of work. Almost all of the images I work with are over or under exposed or are seriously degraded in some other way and have to be restored.

L.L. In one of your previous interviews, you state:

“My take is that the tent that we have traditionally thought of as photography is no longer large enough to contain all that the format is becoming. In this sense, I actually think of myself as a digital printmaker, focused on photography – and on its history and traditions – rather than as a photographer per se. And my images, in my view, really aren’t photographs: They’re digital prints concerned with how the medium of photography has shaped the way we frame our perceptions of the world.”

L.L. I find this very interesting! Like others, do you feel that we are on the verge of some kind of post-photographic shift?

P.B.L. I’m still working through what that would look like and what the ramifications might be. For example, you have the CEO of SnapChat speculating that photography may one day become a common form of daily human communication. It seems then, that photography as a means of artistic expression might, also, evolve into an art form, like graffiti to be ubiquitously vernacular, and anonymous: in the sense that on the internet, “likes” and “views”, not authorship dictate whether or not an image goes viral. Not even graffiti has the advantage of the internet’s reach.

Of course, everybody and their dog with an interest in photography has an opinion about the questions you’re posing here.

In an oft quoted interview, Robert Frank said in Vanity Fair a few years ago, “If all moments are recorded, then nothing is beautiful and maybe photography isn’t an art anymore. Maybe it never was.”

William Eggleston, after he heard what Frank had said, replied, “I don’t disagree with any part of that statement.” Which is like Mozart saying to Beethoven, “When I die, the art form of music will die with me.” After which Beethoven agrees with him.

As an art form, photography, similar to music, is composed of a finite range of visual notes and modalities, infinite in the number of ways these notes and modalities can be arranged and interpreted. Trends come and go, as do tastemakers and critics, but, if given the opportunity, we can only hope exceptional photographic imagery, just like exceptional music or great work in any other medium, will always find a way to rise above the churn to stand the test of time and eventually find an audience.

That said, every vibrant art form or commercial enterprise has to have an economic rationale for being, and the more affordable, ubiquitous, and user friendly a medium like photography becomes the less feasible it will be for a self-sustaining population of professionals to market their wares alongside the copyright free work of millions, if not billions, of amateurs.

And, as in any ecosystem, without a healthy balance of competition and cooperation to sustain it, the professional side of the business, at least as we know it today, will certainly become less relevant over time. In a post-photography world, this may become fine art photography’s fate, relegated to an academic niche market in which commited practitioners jostle for insular recognition and awards – and in which collectors of the medium become as rare as three legged unicorns. Some might argue that this scenario has already come to pass…

This interview was conducted almost ten years ago. It has been edited for length and clarity.

This interview was conducted almost ten years ago. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Images from Peter Brown Leighton’s Search For _ruth Mission series.

All Copyrights Peter Brown Leighton.

Peter Brown Leighton lives, works and perambulates in Lockhart, TX.

•••