Chang Chaotang Retrospective Exhibition At The Taipei Fine Arts Museum – Taipei, Taiwan

Museum Director’s Foreword

Always on the go and first one on the spot –Chang Chaotang has been taking photos ever since high school. During his fifty-year artistic career, he has created works spanning photography, television films, documentaries and feature films. Reflecting the state of the times, his works are also a testimony to history, and have been awarded various important artistic awards, such as the Golden Bell Award (1976), the National Award for Arts (1999) and the National Cultural Award (2011). In addition to curating photo exhibitions and teaching film production, he has planned, edited and wrote series of books about Taiwanese photographers and monographs on photographic subjects. Tireless in passing down, accumulating and promoting the photographic aesthetic tradition, as well as nurturing talents, he has made great contributions and has had a profound influence.

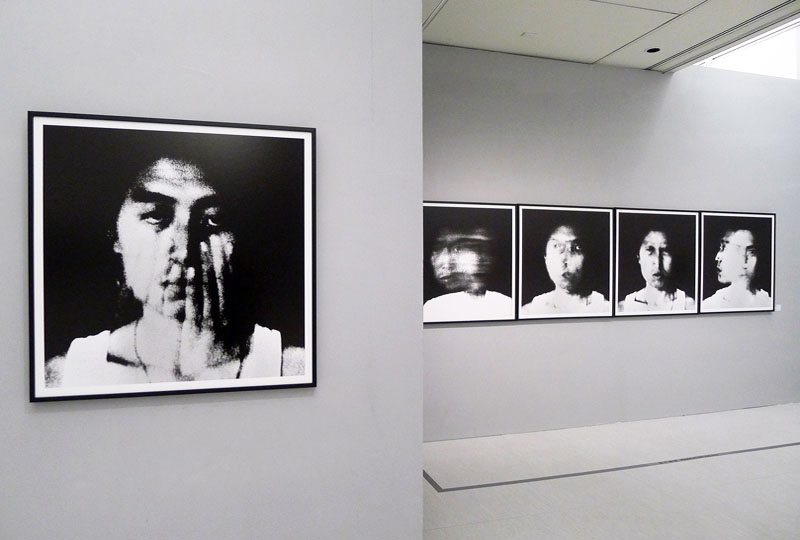

In terms of the existential values of man and the contemplation of people’s temporal and spatial situation, his images are both ordinary and sublime, warm and detached, absurd and humorous, exemplifying the photographer’s keen observations, deep understanding and sympathy, as well as profound compassion and empathy. In 1962, when Chang was standing on his balcony on the loft of his home, the sunset cast his shadow on the wall, with his head cut off. With the camera slung over his body, he used the self-timer to take a classic headless self-portrait. The image is simple, clean-cut and powerful. Headlessness represents a sense of alienation and loss. The headless body is evocative and conveys the modernist sense of isolation and detachment. This visual quality hovering between the realistic and unrealistic has been his distinctive photographic style for over fifty years.

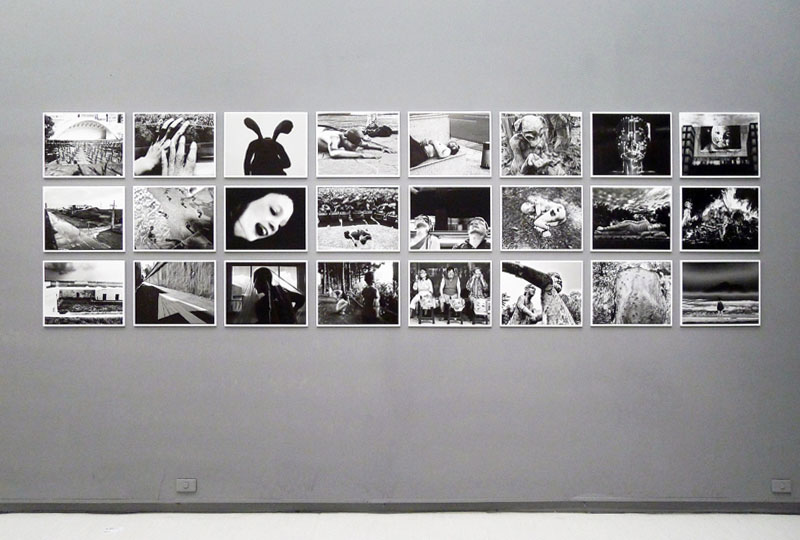

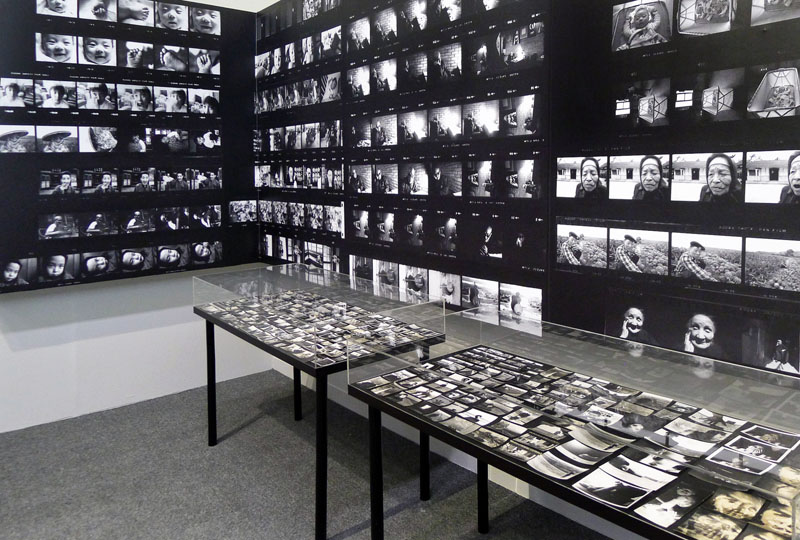

This exhibition, the first complete Chang Chaotang retrospective, features some 400 photographs dated between 1959 and now (including contact prints and portrait series that have never been shown, and composite images taken by the digital camera and cell phone camera); eight documentaries and TV films; and an “exhibition within an exhibition” recreating the settings and installations of highly experimental shows that Chang took part in in the 1960s, such as the Modern Poetry Painting Exhibition and the Informal Exhibition; some original photographs, drawings, scribblings, notes and collages, as well as manuscripts of his monographs of Taiwan photographers, books and posters of his exhibitions. Six themes have been set out according to the chronology and content of works, including Images Of Youth (1959-1961), Existential Voices (1962-1965), Installations, Scribblings And Original Works (1966-1986), Social Memory / Inner Landscapes (1970-2005), Digital Quest (2005-2013) and Faces In Time (1962-2013). With both breadth and depth, they provide a comprehensive picture of the aesthetics and achievements of Chang Chaotang’s images, and his important role as a link between past and future in the development of Taiwanese photography and images.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. The museum will be presenting a series of important exhibitions. Time : The Images Of Chang Chaotang, 1959-2013 is not only a significant event in the photography circle, but also a major artist retrospective of the museum this year. The exhibition is made possible through the whole-hearted support of the photographer and the writers, as well as the assistance of Bright Digital Printing CO. LTD., Steelman Trading, Origin International Arts, Revision Communications and the Daguerre Darkroom Studio, which have generously loaned us photographic equipment. I wish to pay them my respects and thank them heartily.

Huang Hai-Ming

Director, Taipei Fine Arts Museum

••••••

From Manipulating Reality to Questioning Reality

Loose Thoughts on the Photography of Chang Chao-Tang

Gu Zheng

Photographer and Critic

Professor, Fudan University School of Journalism

Deputy Director, Fudan University Research Center for Visual Culture

To critique the photography of Chang Chaotang is a challenge for a critic, but it is also a source of stimulation. His photographs are open. They do not limit the vision of the viewer. Quite the contrary, they spur the viewer’s urge to articulate, and open wide the viewer’s vision. His photos make a person feel that reality, passing through his gaze, has been unveiled in a way (or even many ways). His gaze allows one to discover that photography really does possess the potential to transform people’s perceptions of reality. This magical ability to transmogrify reality may bring about two different possibilities, in photography and in comprehension. For someone who takes pictures, how to transform the things of reality — to move from simple documentation toward the fabrication of documentation — is a challenge. And for the viewer, it also a challenge to transform what has already been frozen as an image of reality into something that belongs to an inner reality of one’s own.

For Chang Chaotang, photography is actually the practice of making the concrete objects and events of reality unrestictedly approach a different mode of reality through the transformation of images. This is a practice of endeavoring to achieve the synthesis of two realities. In many circumstances, this method of expressing the personal psychological reality of the photographer in images may be labeled as surrealist imagery. As the American philosopher Arthur Danto noted in What Art Is: “Sur-reality was a kind of psychology of reality, hidden from the conscious mind, and it was on this psychological reality that the Surrealists felt true art is based.” (Arthur C. Danto, What Art Is, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 2013, p. 13).

The reason we are stirred by photographs such as Chang Chaotang’s is that in many situations surrealistic images may transcend the surface images of reality we can grasp, and express images that go beyond reality. In these surreal images, the secrets of the world may be revealed a little. This challenges a photographer’s power of vision, and tempers it.

I believe that the purpose of surrealism is not to give people an awakening shock by making the ordinary seem unfamiliar, but rather to make us see that the world has always been unfamiliar and bizarre. We believe this reality to be commonplace and familiar, but that is because we have not delved down deep into the depths of reality. The familiar appearance we complacently, or perhaps unthinkingly, consider the world to have is not its fundamental form, nor its true form, but may be described as the true form of its surface. Once we are able to delve into the deep levels of reality, then strangeness becomes axiomatic, and so-called familiarity can never again find shelter in our minds. The world in the eye of the surrealist belongs to both their psyche and the everyday, and is a part of their psyche and the everyday that ought to be shared with everyone. The only thing is, once they have captured these unfamiliar everydaynesses inciting uncertainty regarding reality, it’s up to them to determine what form they should take to be shared or disseminated. People may assume that it is only when they wish to share with others that the world becomes so peculiar, but in fact such is not the case. Reality is inherently complicated.

Different means and methods of viewing will bring about different worlds. The viewer’s own aptitudes and worldview often make it so that the world they wish to share with us is different as well – just like the photos of Chang Chaotang that tell us of the world’s absurdity. Those who are able to comprehend such an irrational, preposterous world will naturally delight in it, while those who cannot comprehend it will remain bewildered. This is rooted in a difference of worldviews, in a difference of life experiences, and in a similarity of individual subjective identities.

The photographs of Chang Chaotang do not alter reality in the least. Yet because they alter the image of reality within the picture, these photos also alter people’s perceptions of reality, and interject themselves within the psychic reality of the group. He uses the abnormal to subvert the normal. Thus, he refutes the normal and also attests to the universality of the normal. Through surreal images he unearths the paradoxical nature of reality. Thus, he refutes reality, but also affirms the puzzling, ungraspable nature of reality. Chang Chaotang’s photos have always revealed a pessimistic tone. Yet his enormous pessimism has not hindered his great passion for manifesting his own pessimistic vision — this is the major form he has adopted to fight back against the world. He uses intrinsic nothingness to resist the seductions of reality. He uses an innately ludicrous vision to measure the mediocrity of reality, igniting the stifling night air with realizations and “skewed perceptions” of quotidian life. The history of art is actually the history of skewed perceptions. That which is normal, that which is ordinary, cannot form a skewed perception. And even more paradoxically, it is often the skewed vision that suggests the true form that is more universal and, of course, buried more deeply. Those who relish the “true form” that exists on the surface will discover that this is clearly not the work that Chang Chaotang’s photography attempts to undertake.

Chang Chaotang’s photography is deeply connected to the issue of how the Taiwanese of his era understood “modern,” “modernism” and “modernity.” It was a modernism in which even the word modernism itself needed to be questioned. And surrealism, rich with portentous images, provided an important revelation of the meaning of modernity. To put it thusly is not to place surrealism within the confines of modernism, nor to place the two in opposing positions, but to emphasize that only by understanding surrealism in this light can one gain a fresh recognition of modernist photography and the work of Chang Chaotang. In a sense, photos such as Chang’s are both guideposts allowing us to enter the labyrinth of surrealism, and a path to a better understanding of modernism. And Chang’s photos presented a visage even more unique than the compelling aesthetic of modernism.

Surrealism, in my view, is one of the sources of nutrition that Taiwanese modernist photography has absorbed. Even though the era in which Chang lived as a young man, owing to Taiwan’s political situation, did not give particularly free rein to modernism, ultimately it did afford a certain amount of room for modernist activity. Therefore, Taiwanese artists including Chang Chaotang did have the opportunity to notice the existence of surrealism and to put into practice their own understanding of it, allowing a dialogue to unfold. Among the members of V10 – what might be described as the earliest group of Taiwanese to raise the banner of modernist photography – Chang Chaotang’s photography may be the coldest, in terms of tonality. Yet his coldness vividly conveyed the temperature of Taiwanese society’s mindset as a whole. Given the intense oppression of the government, the very existence of modernist art, including photography, was a form of resistance in itself.

In critiquing the historical impact of surrealism, the French historian Patrice Higonnet commented: “The greatest benefit of surrealism (considering itself to be a groundbreaking revolution yet ultimately reduced to a form of bourgeois entertainment and consumption) was that it informed us of Europeans’ psychological state of tragedy following the great slaughter of 1914-1918.” (Patrice Higonnet, Paris: Capital of the World, Commercial Press: 2013, p. 384) Likewise, a corresponding aspect of Chang Chaotang’s work is that he captured exceedingly time-specific photos of Taiwan, which may be seen as a portrait of the “psychological state of tragedy” of Taiwanese people during a time of intense political oppression. The unease, powerlessness, falsehood, consternation and rage projected by society as a whole under the double assault of external pressure and internal nervousness all found expression through his photographs, calm and disciplined yet greatly “transformed.” And in today’s post-martial law era, the basic meaning of people’s hopelessness, and the photographer’s profound understanding of the bitterness and absurdity of life, are still the very core of his photography’s focus and expression.

For example, among Chang’s works can be found three “headless” photos taken in different periods. If one were to view these three images side by side, one might discover his basic view of people and life. The two earliest photos were taken in 1962. One shows a person’s naked back, the slick torso forming a visual conflict with the rugged, hard mountain rocks. The other photo is a dark silhouette of the upper half of a body, a distant mountain ridge seemingly slicing off the skull horizontally like a sharp blade. These two pictures seem to explain the dejection of human desire – substantive yet illusory. Yet the opposite of the body is the spirit (brain), the value or meaning of which does not exist, or if it does exist, it is filled with the danger of being cut off. If these two pictures manifest the photographer’s superlative ability to produce bizarre images of people, then Fangliao, Pintung, photographed in 1980, provides a collective image of headlessness. This image comes from a certain split second when a group of people were doing some kind of group exercise on a beach. Chang Chaotang interjected his camera lens into this ongoing process, suspending time, and stripping away the concrete meaning of the event, leaving only the extant scene exposed. Making the concrete event lose its concreteness and placing the meaning of the event in a state of suspension, this photo fully embodies his consistent viewpoint of people, and points out his basic method of photography. Perhaps it also communicates criticism of the headless masses. If we were to place this photo next to Eugène Atget’s picture of a group of Parisians gazing up in unison at a solar eclipse, we would find a similarity in both their method and concept of expression. Deconcretizing concrete events, suspending concreteness and meaning, he cut off the connection with concreteness, and in so doing produced a form of meaningless meaning. From the image of a headless individual to the image of a headless crowd, Chang Chaotang, living in the era of martial law, finally articulated the fundamental view of people and the fundamental critique of time that had haunted his heart for nearly twenty years. Infatuated with the flesh, the spirit is severed. Perhaps this is one of the viewpoints he wished to share with us.

In terms of its true meaning, surrealism’s objective is to change life, and also to change the world. To a certain extent it has already proclaimed the failure of its own artistic mission, yet such an artistic mission remains revelatory. Its determination to open the eyes of the soul deserve respect. Through a confrontation with the visual, it has changed people’s perceptions of the world and of life. And while Chang Chaotang may never have harbored the ambition to change the world, his aspiration was surely to change people’s perceptions of the world through a unique way of looking at things. This visual praxis, to some degree, took part in a practical effort to change the world. The true meaning of surrealism is to look squarely at one’s reality, to bravely face reality and through visually subversive methods, to produce a visual insubordination to reality. Whether it be the suffocating sense of political suppression of the martial law era, or the sense of weightlessness when society shook off its pressures after martial law was lifted, both require artists to embark from their own predicament and standpoint and proclaim their own visual declaration regarding life and reality.

Chang Chaotang’s method of doing photography is not to proceed from a concept in order to achieve an external appearance in conformity with modernism, but rather to begin by considering individual physiology, intuition and everyday experience, to criticize and poke fun at the real world, and to transcend reality through his subversive presentation of the everyday. His photography sets out to examine the act of photography itself and the language of photography, while expressing his views of both photography and the world. Chang Chaotang’s surrealism is an ingenious manipulation of the elements of reality as he sees them, engaging in criticism of reality through the form of visual deception. It is a form of reality manipulation. By its very nature, modernism bespeaks an attitude toward reality. And even the meaning of the word roots composing the word surrealism suggest that it encompasses an attitude toward reality. Of course, it cannot be simplistically understood as a transcendence of reality. Transcendence can sometimes be seen as an escape from reality. But Chang Chaotang’s photography is something else entirely, a realistic unearthing of reality, an article of reference causing reality to transcend reality.

One of the basic methods of realistic photography is to emphasize a true-to-life representation of reality. Historically, it challenged the “manipulation of reality” that took place in the aesthetic of salon photography. Modernist photography renovate the public’s visual experiences, but people frequently equate this renovation of visual experience as a questioning of reality. In fact, such is not the case. To call attention to the hidden inner face of the world, we often need a more resolute courage and determination to break with reality, to duel with reality. And surrealism has always questioned the basic nature of reality, and through such methods as photography, it goes further to manipulate reality so that it becomes a questioning of reality that enjoins us to face reality and ourselves straight on, and also to refute reality and ourselves in a variety of ways, so that we not only achieve a transcendence of ourselves, but also transcend the shackles that reality places on human perception and behavior.

Chang Chaotang is passionate about getting out on the street. As I recall in 2011 when he visited Shanghai, no sooner had he set down his suitcase than he went out by himself onto the street to take pictures of the scenes. Fundamentally, Chang Chaotang is a street photographer. In general, photographers can be divided into two categories based on their work method. The first kind goes into different public venues where people are active, observes the behavior of people and captures their every movement, producing the photographer’s own documentation, observation and evaluation of reality. For them, the street is an important place of work. This is spontaneous, observational photography. The other kind of photographer builds or dwells in a closed-off house, then takes pictures of people whom they have asked to perform according to strict arrangements. This is fabricated photography. Judging from Chang’s work method, he clearly belongs to the former group. The street is his studio and his prop box, and his reception hall too. Most of those miraculously captured photos of his come from the streets or public places of Taiwan. Through his masterful combination of spaces (his visual compositions), both people and objects reveal a distinctive sense of reality.

Just as the surrealists of Paris chanced upon the strangeness of people on the streets of Paris, harvesting an abundance of objects with their cameras and producing a complexity of images, the real life in Chang’s photos is equally bizarre and surprising. His photographic vocabulary spans the array of human life and death. Fundamental pessimism is the base tone of Chang’s photography. These pessimistic emotions permeate and surface from the film paper, overflowing with the silver light of despair.

And the streets of the modern city are eternally waiting for the kind of photography who anticipates an encounter with an “accidental harvest.” Chang Chaotang has discovered that on the streets can be found not only the fragments of matter that humanity has abandoned, but samples of the human spirit. Careless people sometimes assume they have cleverly covered up their own secret worlds, when in fact they haven’t. Through the sharp eyes of Chang Chaotang, we’ve discovered that human beings are still a tribe digging in their own buried desires and thoughts. Of course, what he has discovered and recorded has not only revealed the secrets of humanity, but also to a certain extent exposed his own inner secrets. But this does not matter, because he takes joy in being a part of humanity, evaluating and examining the spiritual activity of humanity, and making it visual. He is one of the few photographers who can in some way communicate his own sense of premonition regarding reality. We need these kinds of prophetic photographs.

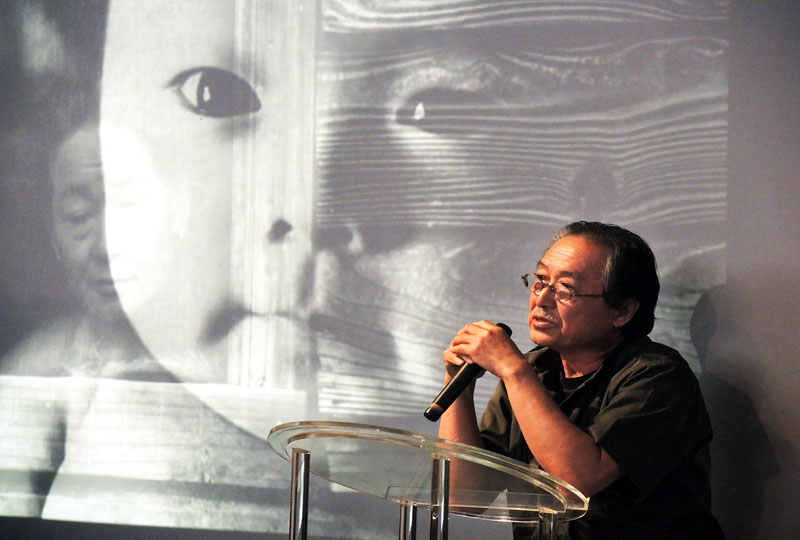

The Existentialism of Chang Chao-Tang 張照堂, Taiwan

The Taipei Fine Arts Museum is currently presenting the first comprehensive retrospective solo exhibition of one of Taiwan’s finest photographers Chang Chao-Tang 張照堂. Time: The exhibition The Images of Chang Chao-Tang 1959-2013 features over 400 works of photography from 1959 to today, as well as eight documentaries and television episodes. It also features two experimental installations from the 1960s. The exhibition is presented in six major themes: Images of Youth, 1959-1961; Existential Voices, 1962-1965; Installations, Scribblings and Original Works, 1966-1986; Social Memory / Inner Landscapes, 1970-2005; Digital Quest, 2005-2013; and Faces in Time, 1962-2013.

Primarily a street photographer, Chang Chao-Tang’s work has been described as prophetic, and a modernist reflection of an absurd reality. His approach is a synthesis of western surrealism and existentialism with Chinese ideology. Chang began taking pictures as a teenager in high school and much of his work reveal the irony of life and death. In his interview with Taipei Biennal 2012, Chang says his imagery depict loss, finding affinity with Taiwan’s Lost Generation. He also says political references to the social impact of Taiwan’s 4 decades of martial law as interpreted by audiences are indirect. His photography represent more ‘a status concerning life and human beings, a status of being self’.

Time: The Images of Chang Chao-Tang, 1959-2013 is currently exhibiting till 29th December 2013 at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, No.181, Sec. 3, Zhongshan N. Rd., Zhongshan Dist., Taipei City 10461, Taiwan, R.O.C.

Posted on Invisible Photographer-Asia, November 24, 2013

Breathing Different Air – Chang Chao-Tang 張照堂, Taiwan’s Master Surrealist.

Interview by Kevin WY Lee. Translations by Sebastian Song & Valerie Wong.

The Taipei Fine Arts Museum is currently presenting the first comprehensive retrospective solo exhibition of one of Taiwan’s finest photographers Chang Chao-Tang 張照堂. Time: The exhibition The Images of Chang Chao-Tang 1959-2013 features over 400 works of photography from 1959 to today, as well as eight documentaries and television episodes. Chang has been described as a master in surrealism. His body of work, a synthesis of western existentialism and Chinese ideology, is hailed as an iconic sign of the times during Taiwan’s White Terror period.

Chang Chao-Tang’s influence extends far beyond his own photography practice. Chang is also credited with being a strong mentor and curator to many young Taiwanese photographers. He has also written and published an impressive array of essays and books on Taiwanese photography. In our own collection of Taiwanese photo books his name appears in every single one, in form or another. In this exclusive interview we talk to Chang about his achievements and photography in Taiwan.

You started taking photographs very young in high school after borrowing your brother’s camera. Were you talented to begin with or was it learnt and nurtured?

In 1958, my brother’s camera provided me an excuse to have fun during weekends. It was a much needed stress relief from my hectic school life. I didn’t feel my photos were any good then so all the negatives were discarded. Thankfully, I kept some prints which were scanned and archived accordingly.

Do you think it is important for audiences to understand the photographer’s work and motives?

Probably more so for contemporary photography. It is, however, not necessary for the other genres. Sometimes the more we understand, the less tasteful the works become.

You have worked on posed photographs and candid street photography. Is there a difference in the approach for you in terms of creating the image?

It is the choice between objectivity and subjectivity. A conscious decision whether to participate as a master of staging or just a silent observer.

Magnum photographer Chang Chien-chi said in an interview with Taipei Times that there is a danger in being too subjective because you can become too stylish. What are your thoughts on that?

There is an over emphasis on speed, resulting in a highly competitive atmosphere. Individualism soon takes over and stardom beckons. Everyone wants to command the lead role while the willingness to be part of the supporting cast dwindles. But it is the continuing development and accumulation of experience that will eventually strengthen the community.

You were awarded the 30th National Cultural Award in 2011. How does it feel as a photographer to receive such an important cultural award? And do you think your images reflect the culture and spirit of the people of Taiwan?

I heard the jury’s decision was unanimous and I felt most honored. My images reflect my life views and cultural awareness. The images are influenced by Taiwan’s diverse society, its many faces and the emotions invoked.

You were also awarded the National Award for Arts in 1999, the first time it was awarded to a photographer. Was it controversial? And how is photography viewed in Taiwan’s Art community?

I heard the jury was not in agreement but the liberal and progressive faction claimed victory. That was an encouragement for the photography community. Taiwan’s photography community is similar to that of other countries, keen on reality, honesty, beauty, landscape and life. Photographers serve these themes and actively expand their horizons. Some photographers approach photography as a recreation. Some view photography as a technical exercise. Others embrace it as life. This diversity, however, does not aid or facilitate the exchange of ideas and craft.

Do you think most great photographers or artists are conflicted people? That great work can only come from a place of turmoil and conflict?

Turbulent times easily give birth to heroes but heroes require talent, willpower and hard work. Even during peaceful periods, one’s life can be one of loss and conflict.

In your essay, you said ‘Photography is intrusive. For a photographer, the camera is a necessary evil. Its gains also brings about losses.’ How should a photographer address this to find a balance?

I think it is only possible by being more humble and expressing greater gratitude.

Can you tell us about your obsession with the theme of ‘Time’?

My theme is ‘Life’. ‘Time’ is secondary. A good photograph should be free from the bonds of time and space. Thus I am obsessed with the various stages of life, its prosperity and decline, its growth and decay.

You have worked with still photography and motion pictures. What are the differences between the two and which one do you prefer?

Motion pictures are about time lines. They represent the strength of continuity. Photography is about a moment. It is more liberal, simpler and independent. Thus it is more difficult to capture an unique moment, especially one with meaning or imagination.

In your most recent images, you’ve photographed in colour after years of black & white photography. Why did you switch and was transitioning to a world in color difficult?

Digital cameras are color by default. Color was never an issue and I didn’t avoid it. Content, however, is difficult.

Can you tell us about your process when editing photo books?

I start off by selecting the presentable images. Then I seek a balance of elements including content, style, composition, lighting, and texture. The harmonization process is continuous and laborious. However, I occasionally sense editorial mistakes from earlier years and felt there is a need to amend them.

Critic Kuo Li-Hsin compared some of your work to Gary Winogrand, Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander. What are your thoughts?

They are essentially three very different photographers. I prefer Robert Frank because he was the earliest, the most direct, and the most unconventional. Timeless while reflecting great artistic elements, his works are highly narrative and profound.

Kuo Li-Hsin also said that the only photography in the private sector that was allowed and promoted was Salon Photography because they were apolitical. How was your relationship with the Salon community and how did they view your work?

Salon photography represented mainstream photography during Taiwan’s White Terror period. It is lifeless and did not progress. Now it is a branch of Taiwan photography. I have no issues with the Salon community though they probably view me as a rebel, a freak. We just breath different air.

Can we say that you employed Surrealism as a way to disguise your ideology during Taiwan’s long period of oppression and censorship in the 1950s to 1980s?

The choice of absurdity and surrealist approach reflects the ideology and oppression of the times. My imagery serve as a confession of the anger and loss felt by the youths within a conservative and bored political reality. I want to articulate the very essence of life through questions and doubts.

Yeh Ching-Fang, a photographer you mentored said you are excessively rational and don’t have a sense of humour. Do you agree with him?

If I am excessively rational, my photographs will be very different. I am, however, not someone who engages in small talk. Then again, many have spoken about my sense of humor reflected through the dark humor in my photographs. Being rational is probably a combination of my creative attitude and appearance to the world at large.

You mentor and curate a lot of Taiwanese photographers. Can you introduce us to the work of a selection of Taiwanese photographers who represent the next generation?

Hung Cheng-Ren’s Melancholy Field series from 2002, Shen Chao-Liang 沉昭良 worked on his STAGE series for 5 years, and Liu Chen-Hsiang 劉振祥 explores the mystery of life in his Scenery Of Life series. More selections on Chang Chao-Tang’s Blog: Chen Shun-Zhu 陳順築; Chen Bo-Yi 陳伯義; Wu Zheng Zhang 吳政璋; and Tseng Min-Xiong曾敏雄.

Posted on Invisible Photographer-Asia, December 16, 2013

Art In America : REVIEWS : April 30, 2014

Chang Chao-Tang

TAIPEI, at Taipei Fine Arts Museum

by Mieke Bal

Time: The Images of Chang Chao-Tang, 1959-2013 celebrated the Taiwanese photographer’s 70th birthday and the museum’s 30th. Chang began to take pictures in 1959, while still in high school. This was during Taiwan’s long period of martial law, known as the White Terror, which ended in 1987. Until recently, Chang executed his work in stark, shadowy black-and-white, fashioning a transformation of reality; his interest was in depth and strangeness rather than surface appearances. Eerie landscapes, strange rock formations and groups of people, obliquely lit, enhance the surrealist quality of many of the photographs.

This was not an exhibition that allowed a routine walk-through visit. Although it followed a chronology of sorts within a spacious display of some 400 works—photographs, videos, contact sheets, cameras and other paraphernalia—the show’s visitors were encouraged to look for something other than the artist’s development. Section titles such as Social Memory/Inner Landscapes, Existential Voices and Faces in Time keyed to the issues that make these consistently lovely images both critical and revealing. Many of Chang’s subjects lack a visible head or face. Headlessness is a common trope in surrealist photographic portraiture—a way for artists to reject a focus on the individual personality. One thinks of Francesca Woodman, to give a telling example. Woodman’s “crossed-out” self-portraits, set in interiors and often modified by superimpositions, appear to express the artist’s desire to merge with the space—with walls, chimneys and torn wallpaper.

In striking contrast, most of Chang’s works depict people other than himself and are set outside. Austerely critical of society’s absurdities, they show no trace of longing or desire. In three works from 1962, a figure is photographed in extremely shallow depth of field, his head bent so that the body seems to end at the neck. One image shows him standing on a ledge with a horizontal orientation that parallels the pavement in front of him and the clouds behind him, into which he seems to merge. In the second image, the man—in the same pose—is enlarged and cropped, leaving only the trunk of his body, looking like a violin à la Man Ray. In the third, a near-negative, he is reduced to a white outline, vaguely suggestive of the chalk contour around a dead body, although he is standing.

Though Chang’s photos have been called pessimistic, such an assessment goes against the grain of their perfectionist beauty. Original and often keenly surprising, they demonstrate an eagerness for exploring people’s subtle interactions with each other and nature. A work from 1966, in which a group of men—all white-shirted but for a slightly isolated figure in a checkered shirt—turn their faces away from the camera, displays with a minimum of means the sensation of exclusion within social togetherness. Another group portrait, from 1988, shows figures with their backs turned, clad in black robes and hoods, confronting a landscape with a threatening sky, whose stormy mood seems to transmit into the anonymous crowd. The look this artist casts on the world of Taiwanese modernity is neither negative nor tender; it lacks all sentimentality. Instead, it is one of wonderment, as he decomposes, transforms and in the end lifts his subjects from routineness. Chang has mentored many, and photography by the following generation in Taiwan is stamped with his mark. Yet his influence, generosity and openness have not resulted in the formation of a distinctive school. This landmark tribute paid homage to a key figure in Taiwanese art, one worthy of international acclaim.