Chang Chaotang In The News

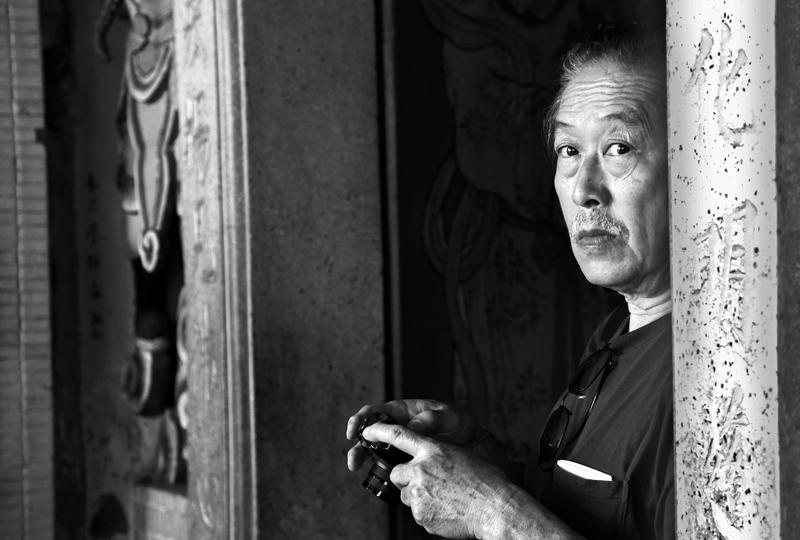

Photographer/Filmmaker Chang Chaotang is featured in an article by Pat Gao for Taiwan Review.

Chang Chaotang’s career parallels the massive changes seen in Taiwan’s society over the past fifty years.

Like An Electric Shock : Chang Chaotang Documents Fifty Years Of Social Change

Taiwan Review (link to online feature).

Below is a transcript of the article. All Copyrights Taiwan Review.

Like An Electric Shock : Chang Chaotang Documents Fifty Years Of Social Change

By Pat Gao for Taiwan Review.

While few people have the talent to emerge as a leader in the fields of photography or cinematography, fewer still are those who manage to master both endeavors. Chang Chaotang (張照堂), however, is one of the rare individuals whose talent is equally apparent behind both kinds of lenses. Chang’s career is also noteworthy because it parallels the massive changes that Taiwan’s society has seen over the past 50 years.

Chang was born in 1943 and first picked up a still camera in 1958, when he graduated from junior high school. As a beginner, he took mostly conventional, or “warmer” photos, as he puts it. In 1961, he entered Taipei’s National Taiwan University, where he majored in civil engineering and continued developing his photographic ability. Soon his style began changing to feature a distinctly “cooler” touch of expressionism, resulting in somewhat grotesque images of headless or handless human figures. “As a university student fascinated by Western concepts such as existentialism, I was more likely to make a bold attempt at subversive or unruly works that resulted from my own arrangement of a picture instead of trying to depict reality objectively,” Chang recalls.

In 1965, exhibitions of photos by Chang and Cheng Sang-hsi (鄭桑溪, 1937–2011), who taught the student photography club Chang joined in senior high school, created a sensation in local art circles due to their nontraditional, abstract style. Chang says he took such photos out of “a drive to comfort his mind” during a time of “dejection and emptiness.”

The images of Chang’s early career reflected his views and concerns about Taiwan’s society, which was then under martial law. Kuo Li-hsin (郭力昕), an associate professor in the Department of Radio and Television at National Chengchi University in Taipei, says Chang grew up and developed his essential creative skills in an “extremely repressed, gloomy” time when “there was a high-pressure, chilly political environment that was reflected in the era’s nascent photographic culture. Amid such political and cultural doldrums, Chang’s photographic art produced a uniquely sober and lucid high note.”

Art critic Hsiao Chong-ray (蕭瓊瑞) says Chang’s distinct style stands apart in Taiwan’s photographic history because of its “noble spirit and attitude that defied being devoured by the floods [of a distorted age],” a reference to the martial law era. Hsiao, a professor of Taiwanese art history at National Cheng Kung University in Tainan City, southern Taiwan, formerly directed the school’s Art Center and served as head of the Cultural Affairs Bureau under the Tainan City Government.

In 1968, Chang began working as a cameraman and photojournalist for the news department at China Television Co. (CTV), which was founded in Taipei earlier that year as the nation’s second TV station (Taiwan Television Enterprise, the first, was formed in 1962). “After taking that job and being exposed to real society, I began moving [back] to a form of sheer realism,” Chang recalls. “I tried to renew my focus on exploring the fundamental aspect of images as a way of recording and conveying social facts.” He worked as director, editor or producer of news programs and documentaries at CTV until 1981, when he left the station to work as a freelance photographer and cameraman.

Society slowly began opening up in the 1970s, which saw the emergence of a grassroots literary trend toward exploring local themes. Chang recalls that it was a time when magazines and newspapers’ literary pages were bursting with nativist works. “It represented a general social atmosphere seeking more intimate connection with one’s surroundings,” he says. “The attempt to take a closer look at one’s own state of existence was also reflected in other local artistic pursuits such as drama, music and painting.” Although the topics of many works of the time were local, writers and artists also began using Western art concepts such as existentialism, modernism and surrealism to examine their material.

During his travels around Taiwan, Chang filmed numerous documentaries and news programs that explored wide-ranging social issues and examined life in different corners of society. In 1980, Chang was honored with a Golden Horse Award for cinematography for his documentary film on classic Chinese-style buildings in Taiwan. That same year, he also received the Golden Bell Award for his cinematography and editing of a CTV news show about a folk religious ritual in southern Taiwan, in which a large custom-made ship was burned at the seaside to ward off plague. The Golden Horse Award is Taiwan’s top honor for film while the Golden Bell occupies the same niche for television.

In the early 1980s, Taiwanese film audiences began turning away from melodramatic, locally made movies in favor of foreign movies, especially those from Hollywood and Hong Kong. With the nation’s cinema industry thus experiencing a decline, a new generation of filmmakers attempted to reinvigorate Taiwanese films with a more solid sense of reality, shaping what became known as the New Wave Cinema movement.

• Realistic Representations

“At that time, younger directors were trying to break free from film’s then-dominant escapist or politically correct tendencies,” Chang says. “They were moving toward realistic representations of the everyday life of common or disadvantaged people.” In the 1980s, Chang worked as a cinematographer for the New Wave Cinema films A Woman of Wrath (1985) and Last Train to Tamsui (1986), both of which were based on contemporary novels by Taiwanese writers.

A turning point in the liberalization of Taiwan’s society came in 1987, which saw the end of martial law. While it is hard to gauge how much influence the arts had on bringing that momentous change about, New Wave Cinema films certainly reflected a society that was modernizing rapidly.

In the early 1990s, Chang began a series of jobs that included a stint at Public Television Service, which began operating under a preparatory committee in 1991 and was formally established as a station in 1998. In 1997, Chang became a professor in the Graduate Institute of Studies in Documentary and Film Archiving at Tainan National University of the Arts. He served as dean of the school’s College of Sound and Image Arts from 2008 to 2009 and still teaches at the university.

Chang was honored with a National Award for Arts in 1999 for his more than three decades of work in the fields of photography and cinematography. According to comments by the award selection committee of the National Culture and Arts Foundation, the organization behind the prize, Chang was recognized because he was one of the first modern artists in Taiwan to “inject literary, theatrical and poetic concepts into photography.” The numerous experimental and documentary works he created, as well as the exhibitions he organized around environmental and other social themes “recorded an era and social changes, and have elevated photography to a higher artistic level, giving it a greater cultural significance,” the committee wrote.

In 2011, Chang received the Executive Yuan’s National Cultural Award for lifetime achievement in the art of photography. Roan Ching-yue (阮慶岳) is a professor in the Department of Art and Design at Yuan Ze University in Taoyuan County, northern Taiwan. Roan credits Chang for “playing a crucial role in defining the aesthetics and values of the art of photography in Taiwan’s postwar era,” and for helping to make social realism a mainstream photographic approach.

• Subjective Touch

In recent years, Chang has injected a more personal, subjective touch into his photographs to express social concerns. His photo series on the issue of nuclear power, for example, consists of bleak images simulating the wasteland that would exist following a nuclear disaster. Nuclear power has generated heated debate in Taiwan and the topic has been proposed as the subject of a national referendum. “There are different forms of participation in a social movement or protests that can be effective in their own way,” Chang says. “Instead of making an overt appeal, these photos offer my concerns and perspective on the issue in a way that doesn’t undermine their artistic nature.”

The photos in Chang’s nuclear series, like those in many of his other collections, were shot in black and white, a medium he prefers for its qualities of “purity and simplicity.” Chang recalls that he got started in photography by taking black-and-white pictures and developing them himself, which allowed him to control the whole process of creating a photo. In contrast, “taking color photos was more expensive and I had to rely on others to finish the work,” he says. “It’s quite a different discipline, as combining and coordinating so many colors to produce a satisfactory effect is a highly exacting task.”

Chang seldom shoots film these days, but frequently uses digital cameras. In either case, he enhances the contrast of his black-and-white images in post-production to make them more powerful. “In the history of photography, the black-and-white format marked the beginning of the art and still accounts for most of the best works,” he says. Black and white continues to reign supreme in the static world of photography, he says, whereas color is usually indispensable in making movies that endeavor to give a genuine depiction of a site or event.

Making documentaries and other kinds of films requires teamwork, Chang notes, while taking pictures is largely an individual process. That creative control is why he has concentrated more on photography than film. “Documentary films must follow a set of ethical rules and usually examine preset subject matter over a specific period of time,” Chang says. “But taking photos is an unrestricted, absolute act under your full control. That gives you a lot of creative freedom and space to move in.”

Of course, such creativity is wasted if a photographer’s images fail to attract viewers. Fortunately, that has not been a problem for Chang. Pong Yu-shun (彭宇薰), head of the Art Center at Providence University in Taichung City, central Taiwan, for example, says that Chang’s works offer some of the most charming and inspiring evidence of the art’s development.

These days, Chang draws inspiration from literature, painting and music. The concepts and feelings imparted by such art ferment in his mind and later burst forth “like an electric shock” that sparks the process of creation. Chang has been feeling that shock for some 50 years now, and yet shows little sign of slowing down in his quest for images that reveal what he calls the “poetic, unspoken depth of existence.”

Write to Pat Gao at cjkao@mofa.gov.tw

All Copyrights Taiwan Review.